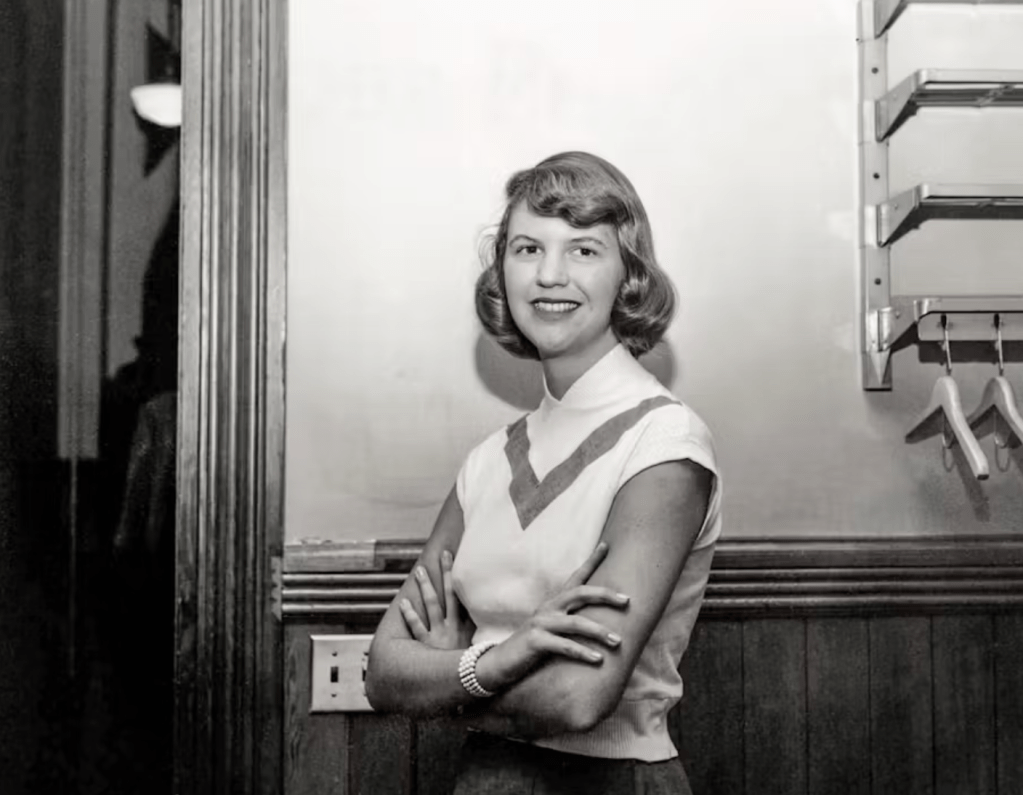

Sylvia Plath – Penrodas Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

The path to self-destruction grows ever steeper in Chapters 10 and 11. Plath’s use of imagery and word choice becomes increasingly more depressive.

The very first line of Chapter 10 paints a bleak picture. “The face in the mirror looked like a sick Indian.”

We find Esther clinging to the bloodied stripes swiped across her cheek from her sexual assault the previous night. It makes me wonder. Is she holding onto the bloodied evidence because the event gave her a shot of exhilaration? Did it make her feel more alive than when she first arrived in New York? Or, is she choosing to not wash her face, because she doesn’t have the energy to do anything but exist. She clearly does not care what the rest of the passengers think of her appearance. She rationalizes her choice, telling herself others look queerer (stranger) than she does.

As the train rolls on she takes in the suburban surroundings. Saying, “It smelt of lawn sprinklers and station wagons and tennis rackets and dogs and babies. A summer calm laid its soothing hand over everything, like death.”

With each turn of the wheels she gets closer and closer to home. The reader can tell she is not excited to get back home. She didn’t want to stay in New York, but she also doesn’t want to go home. If given the choice to go anywhere at all, I am not sure where she would choose. Nothing seems to please her. Her mother meets her at the station and delivers the final blow during the drive home. Esther didn’t get accepted into the summer writing course she had been banking on. Esther is crushed. The entire rest of her summer had been riding on her taking this course, living at college, and getting out of the suburbs so she doesn’t have to share a house with her mother.

Things only get worse. She finds out Buddy Willard has fallen for a nurse at the TB center. Esther isn’t heartbroken to not be seeing Buddy any longer. Even in the break-up Buddy waffles and tells her they might still work out. It could just be an infatuation he holds for the nurse. He throws her an indecisive bone, telling her she can come visit. Maybe that will allow Buddy to see if he really loves the nurse or is just smitten. At least Esther has the self-respect to tell Buddy where to get off in her response letter.

Thus begins her own waffling. Without the writing course, Esther is rudderless. She has no idea what to do with herself. She considers writing a novel, learning shorthand, becoming a waitress and moving to Germany. Her mind turns toward finishing her thesis. She starts to read the voluminous Finnegan’s Wake, by James Joyce. Attributing meaning to passages, phrases, and gibberish, where there is none to be had. She grows so frustrated with the lack of progress on the Joyce thesis she scraps it altogether. Then she decides she should get out of the honors track and just be a regular English major. But that involves studying 18th century authors, of which she’ll have none of. Even getting her degree at the community college seems like too much of a hassle to her. She has no idea what to do, or to become.

She allows herself to be picked up by some random sailor in Boston. Giving him her pseudonym Ellie Higgenbottom and telling him she hails from Chicago and is 30 years old. She tells him lie after lie, even making up a story about being an orphan. She begins to convince herself she will move to Chicago and become Ellie Higgenbottom. She is lost. She can’t sleep, can’t read, can’t write, and the sleeping pills her family doctor gave her aren’t helping. Esther is referred to Dr. Gordon.

Esther loathes Dr. Gordon from the second she lays on him. She tells the reader, “Doctor Gordon’s features were so perfect he was almost pretty. I hated him the minute I walked in the door.” She finds him to be conceited. In many ways, she sees Dr. Gordon as an extension of Buddy Willard. Perfect features, perfect wife, perfect kids, perfect dog, perfect office, etc. As with Buddy and most men in her life, Esther decides she will play a game with him. She will tell him only what she wants him to know. This way, she doesn’t incriminate herself. She avoids giving too much of herself away. She tries to exert as much control over her situation and herself as she can.

He doesn’t take her seriously. He turns to her and says, “Suppose you try and tell me what you think is wrong.” Leaving her to feel that he doesn’t think there is anything wrong with her at all. He is more interested in what college she attended and flaunting his own merits. He tells her he served as at her college for the WACS before he was shipped overseas during the WWII. He has no problem puffing out his own chest. Much like Buddy. Esther doesn’t trust him, doesn’t like him and doesn’t have faith he can help her in any way. Dr. Gordon is not a good fit for her. We sense his treatment is doomed from the start.

Chapter 11 ends with Esther contemplating how one goes about disemboweling oneself. Not a cheery thought on any level.